The Quest for Exactly-Once Event Delivery: Part 1

We’re about to go on a bit of an adventure, I’m not sure how difficult it’s going to be (or if it’s possible), but I’m going to learn some things, and maybe you can learn some things too.

I have a distributed event driven web application FernLabour.com and I want to try and attempt to get an exactly once delivery guarantee for all events that I am generating. Let’s get into it.

What is an event?

An event is an immutable representation of something that happened. They typically represent meaningful state changes in an application.

In my application Domain Events are created when significant happenings occur in a given service such as labour.begun, contraction.ended, or notification.sent. These events are then published to a message bus where other interested services can subscribe to and consume them.

What is an exactly once delivery guarantee?

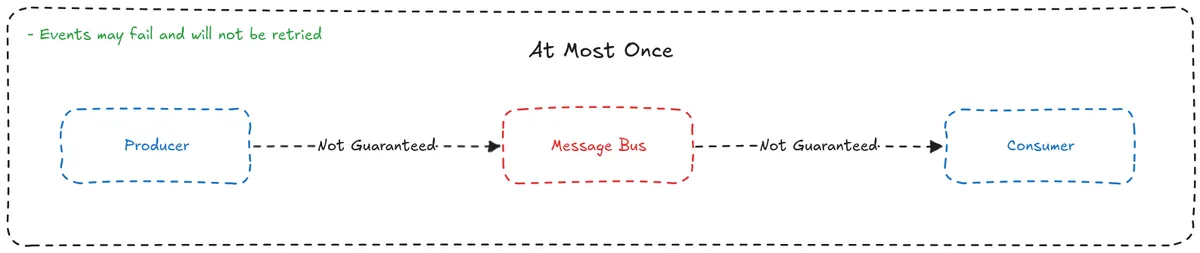

Exactly once delivery is one of the three important delivery semantics to be aware of when discussing distributed systems and events. The three are:

- At-Most-Once

- Events are not guaranteed to be produced or consumed.

- Events can be lost and will not be retried.

- Fine for use cases where minor data loss is acceptable, such as logging.

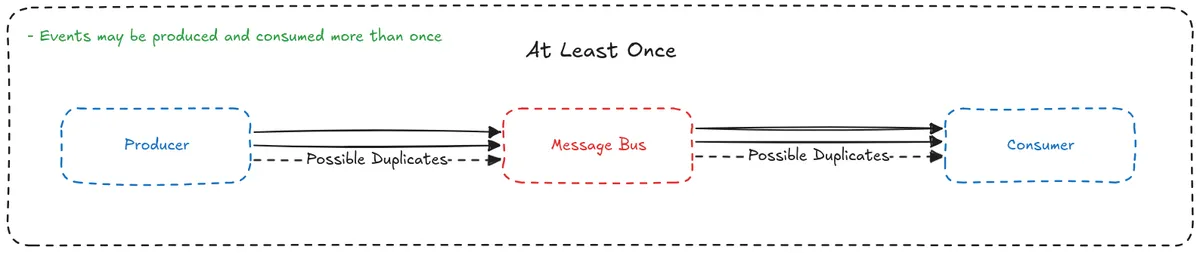

- At-Least-Once

- Events are guaranteed to be delivered at least once.

- Failures will be retried.

- There may be duplicate events on the producer side and the events may be delivered multiple times (or to multiple consumers).

- For use cases where guaranteed delivery is necessary.

- Consumers need to be idempotent so events with side-effects are not consumed multiple times.

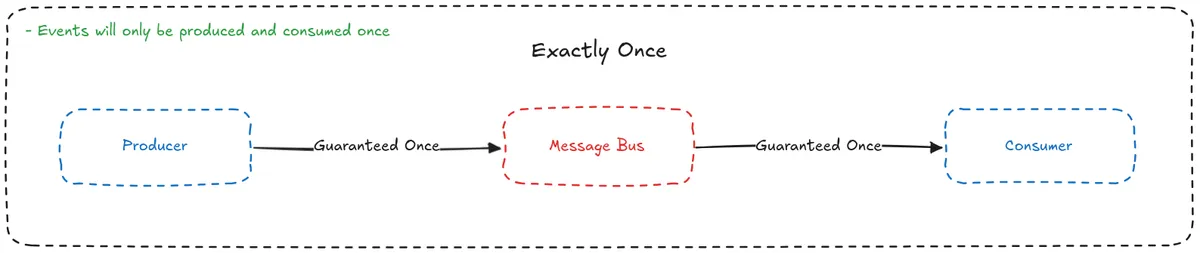

- Exactly-Once

- Events are guaranteed to only be produced and delivered once.

- The most difficult to achieve.

Example request

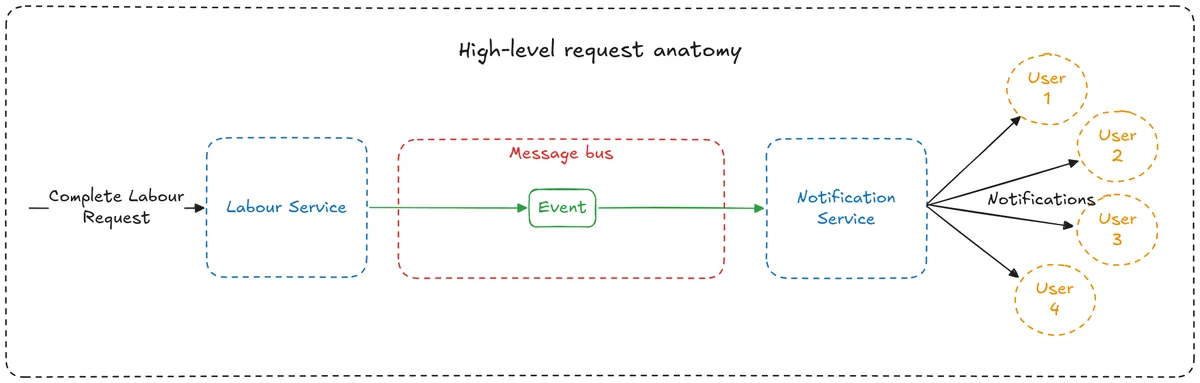

Now that we understand the common delivery semantics, let’s go through an example request at a few levels of detail so we can figure out where we stand right now.

The request we are going to focus on is our complete labour request. At a high level:

- complete-labour request sent to Labour Service from the frontend application.

- Labour Service marks the labour completed.

- Labour Service publishes an event to the message bus.

- Notification Service is subscribed to the topic and pulls the event from the message bus.

- Notification Service consumes the event, sending a “Welcome, baby! 🎉” notification to all interested parties.

Makes sense, Labour Service handles all labour related things like planning, starting, and completing labour.

In this example, the new mum is completing her labour with a request to the Labour Service, which triggers a domain event. Then Notification Service is picking up that domain event and triggering a notification to all of the people who are subscribed for updates.

*this is not exactly how my notifications system is structured, but this makes for a better quality example.

Investigating the Producer Side

OK, now we’ve seen the request at a high level, lets start to drill down into the producer side to see what our delivery semantics are.

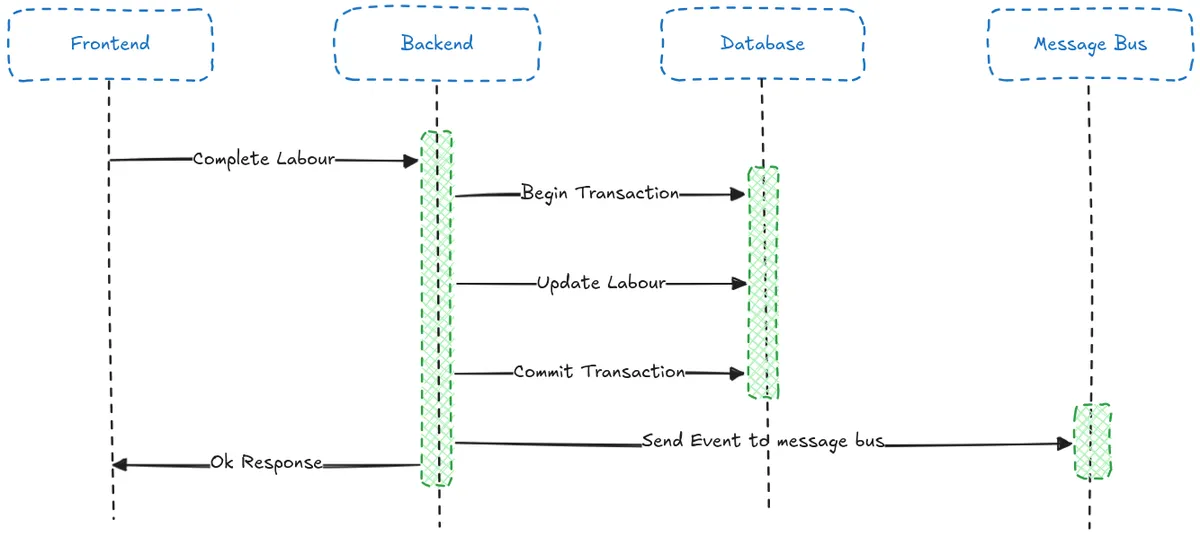

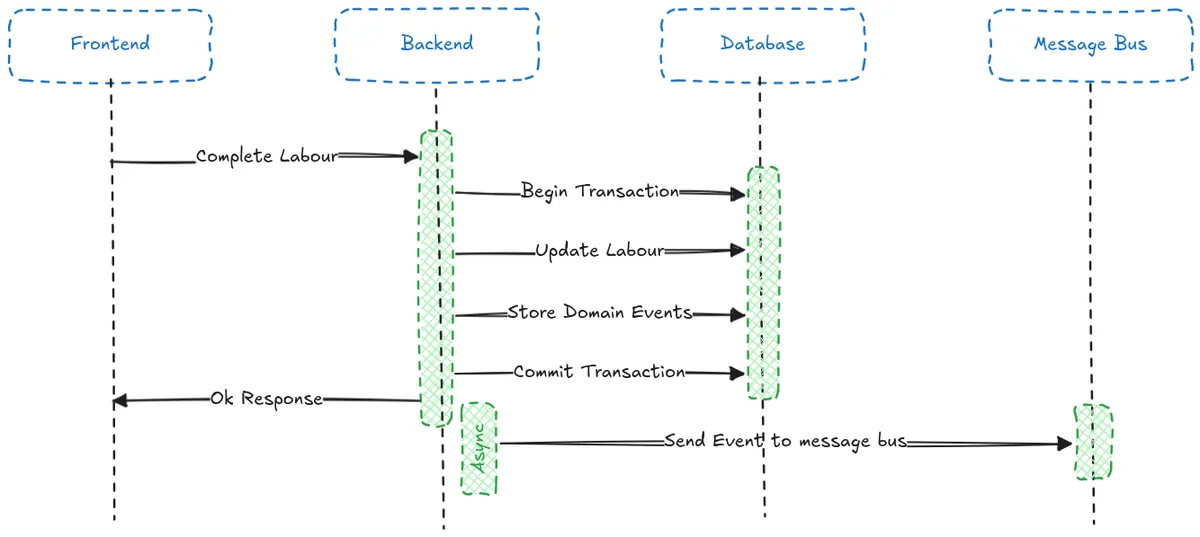

The first three steps from above looks like this in the Labour Service (Backend):

Or, in code as part of a CompleteLabourService application service:

class CompleteLabourService:

def __init__(

self,

labour_repository: LabourRepository,

event_producer: EventProducer,

) -> None:

... # Omitting for brevity

async def complete_labour(

self, labour_id: str, end_time: datetime,

) -> LabourDTO:

# Get the labour

labour = await self._labour_repository.get_labour_by_id(

labour_id=labour_id

)

# Mark it as completed, if allowed

labour = CompleteLabourService().complete_labour(

labour=labour, end_time=end_time

)

# Save it in the database, automatically commits changes

await self._labour_repository.save(labour)

# Produce any domain events that were created in the process

await self._event_producer.publish_batch(labour.domain_events)

# Return a DTO

return LabourDTO.from_domain(labour)Immediately we can see something that could be a problem. We are committing our changes to the database and publishing the event to the message bus separately. What if one of them fails?

Failure Scenarios

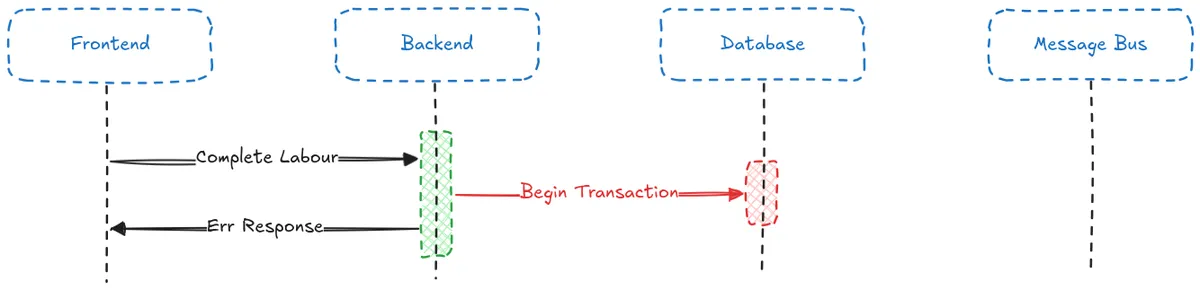

It wouldn’t be a problem if the database failed, we would raise an exception, nothing would be persisted, and the user would be able to try again.

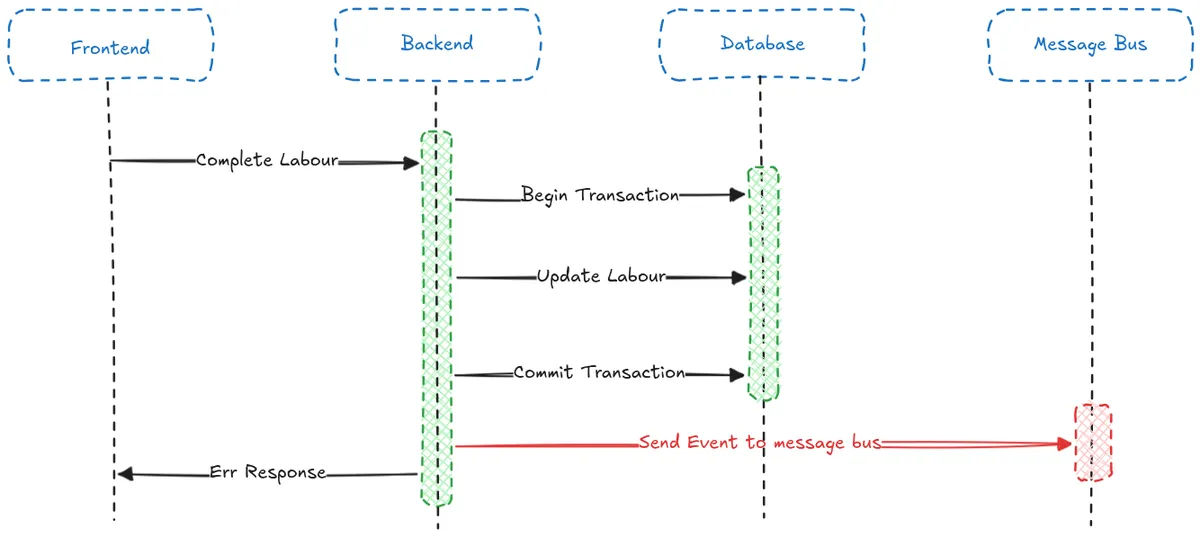

On the other hand, if we fail to publish the event to the message bus then:

- The changes would be persisted to the database

- We would fail to publish the event

- Then we would raise an exception.

In this case the user would not be able to try again, from the perspective of the database the change has already taken place (you can’t complete a labour more than once), and since the event is not being persisted anywhere it would be lost.

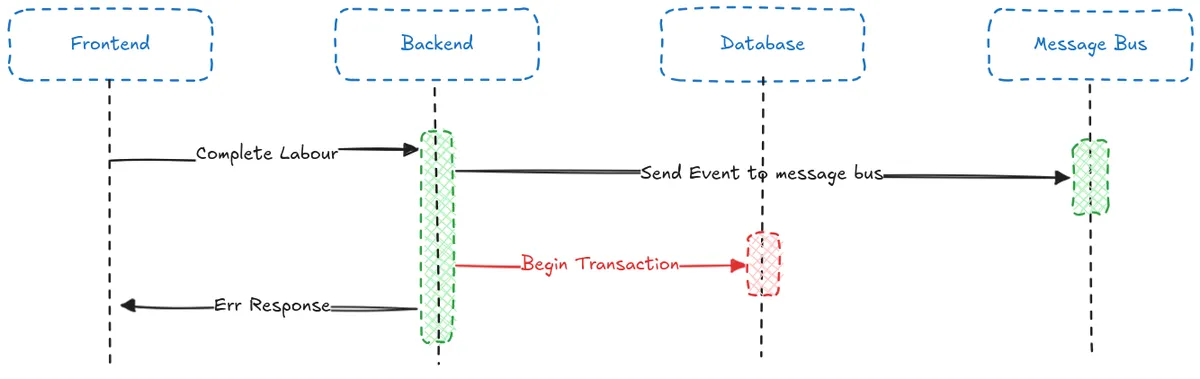

We might naively think that we can just flip the order around so we produce an event first and then persist the changes to the database. However, this would simply reverse the problem, now if the database transaction fails we will have an inconsistency caused by the event being processed downstream wherever it is consumed.

The Dual Write Problem

This is known as the dual write problem and it is going to be our nemesis as we work towards Exactly-Once delivery. The dual write problem occurs when we need to update two disconnected systems atomically, in our case when persisting changes to a database and publishing an event to a message bus, but the same problem would occur if instead of publishing an event we were sending an email, or making an API call.

Since the systems are disconnected we cannot make our updates in a transaction so failures can lead to data inconsistencies that are hard to track down.

Solutions

There are a number of different approaches that you can take for resolving the dual write problem. Examples include Change Data Capture (CDC), which involves listening to changes to the database directly, or Listen To Yourself, which involves publishing events to the message bus and consuming them to update internal state.

I want a simple solution without additional infrastructure to manage, so CDC is out. And Listen To Yourself would involve changes to the frontend to handle state not being updated and returned as part of the request, so that’s out too.

What we are going to implement instead is a transactional outbox.

Transactional Outbox

Instead of publishing the events to the message bus during our request, we will persist the changes to our labour entity and store any domain events in the database in a single database transaction.

These events can then be asynchronously published to our message bus.

Or, in code as part of a CompleteLabourService application service:

class CompleteLabourService:

def __init__(

self,

labour_repository: LabourRepository,

domain_event_repository: DomainEventRepository,

unit_of_work: UnitOfWork,

domain_event_publisher: DomainEventPublisher,

) -> None:

... # Omitting for brevity

async def complete_labour(

self, labour_id: str, end_time: datetime,

) -> LabourDTO:

# Get the labour

labour = await self._labour_repository.get_labour_by_id(

labour_id=labour_id

)

# Mark it as completed, if allowed

labour = CompleteLabourService().complete_labour(

labour=labour, end_time=end_time

)

# UoW is an async context manager that:

# - On Enter: Starts a transaction

# - On Exit: Commits any changes

# - On Error: Rolls back any changes

async with self._unit_of_work:

# Repositories now save the changes but do not commit to the database

await self._labour_repository.save(labour)

await self._domain_event_repository.save(labour.domain_events)

# Spawn a background task to publish events asynchronously

self._domain_event_publisher.publish_batch_in_background()

# Return a DTO

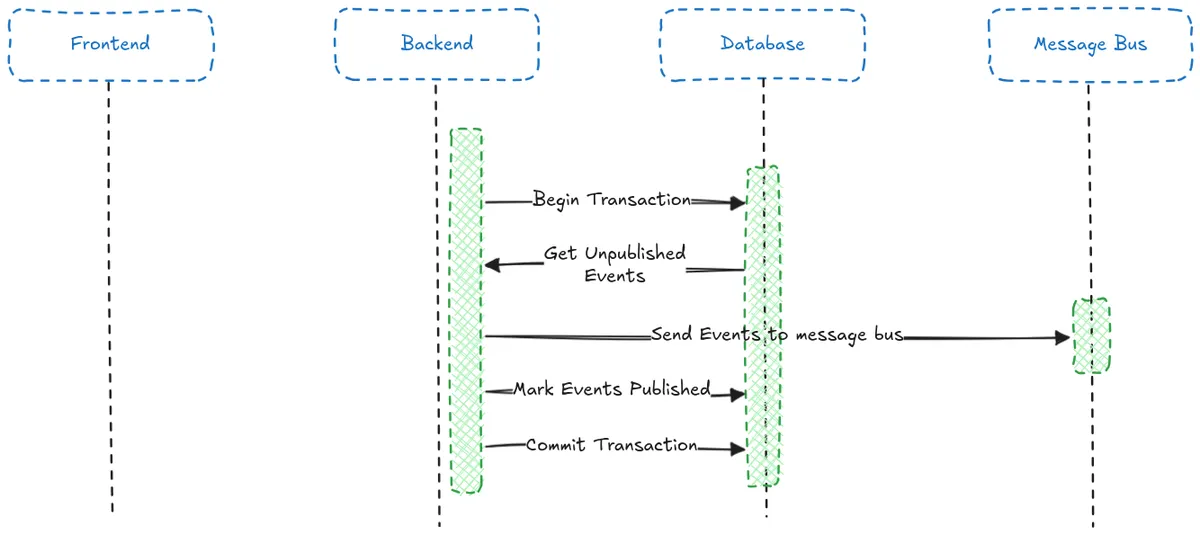

return LabourDTO.from_domain(labour)Our asynchronous processing works by fetching a list of unpublished events from the database, publishing them to the message bus, and then marking them as published in the database. This task can be triggered as in the code example above by spawning a background task from the application service, or can be persistently run in the background to poll for events. I am using both approaches for maximum fault tolerance.

(the green Backend box is intentionally off the line to illustrate that it is running as part of the backend but asynchronously, not blocking requests)

Or, as code:

class DomainEventPublisher:

def __init__(

self,

domain_event_repository: DomainEventRepository,

unit_of_work: UnitOfWork,

event_producer: EventProducer,

task_manager: TaskManager,

) -> None:

... # Omitting for brevity

def publish_batch_in_background(self) -> None:

# TaskManager could be an external task queue like Celery/Dramatiq/RabbitMQ.

# The TaskManager I am using is creating asyncio tasks so I don't need

# to manage or rely on any external infrastructure.

self._task_manager.create_task(

self.publish_batch(), name=f"publish_batch_in_background:{uuid4()}"

)

async def publish_batch(self) -> None:

# In a single unit of work

async with self._unit_of_work:

# Fetch the unpublished domain events

domain_events = await self._domain_event_repository.get_unpublished()

if not domain_events:

# Nothing to publish

return

# Publish them to the message bus via the event producer

result = await self._event_producer.publish_batch(events=domain_events)

# Mark successfully published events as published

await self._domain_event_repository.mark_many_as_published(

domain_event_ids=result.success_ids

)What if the outbox publish fails?

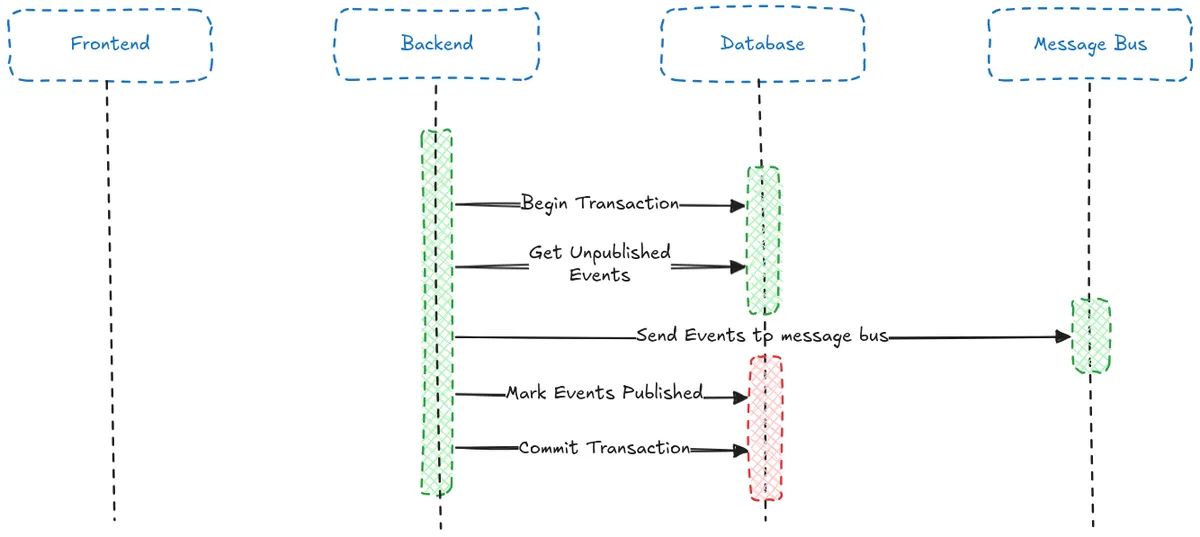

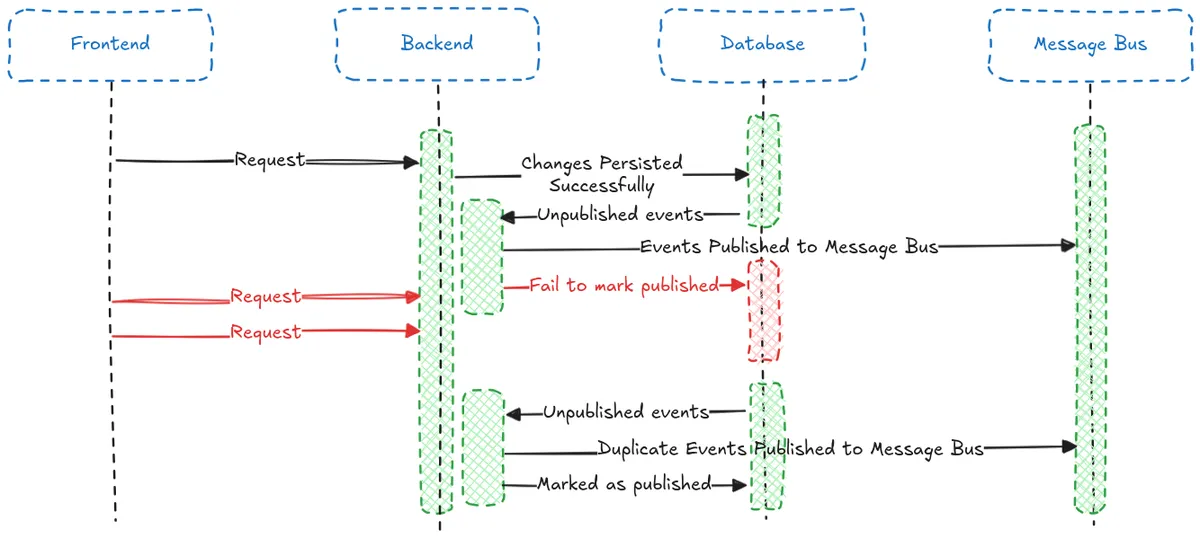

You may notice another potential dual write problem here, what if we fetch the unpublished events from the database, publish them, and then fail to mark them as published in the database?

In this case the events would be published multiple times.

Comparing Risk

With our new transactional outbox and asynchronous message processing we have transitioned from At-Most-Once to At-Least-Once delivery. This is not the Exactly-Once delivery guarantee that we set out for, but looking at it this way doesn’t capture the whole picture. We need to compare the actual risks: losing events vs publishing them more than once.

We are using GCP Pub/Sub as our message bus and GCP Cloud SQL (PostgreSQL) as our database. Both services have monthly uptime SLAs of ≥99.95%. This means that in any given month, they could be down for around 22 minutes (pretending that SLAs are guarantees for simplicity).

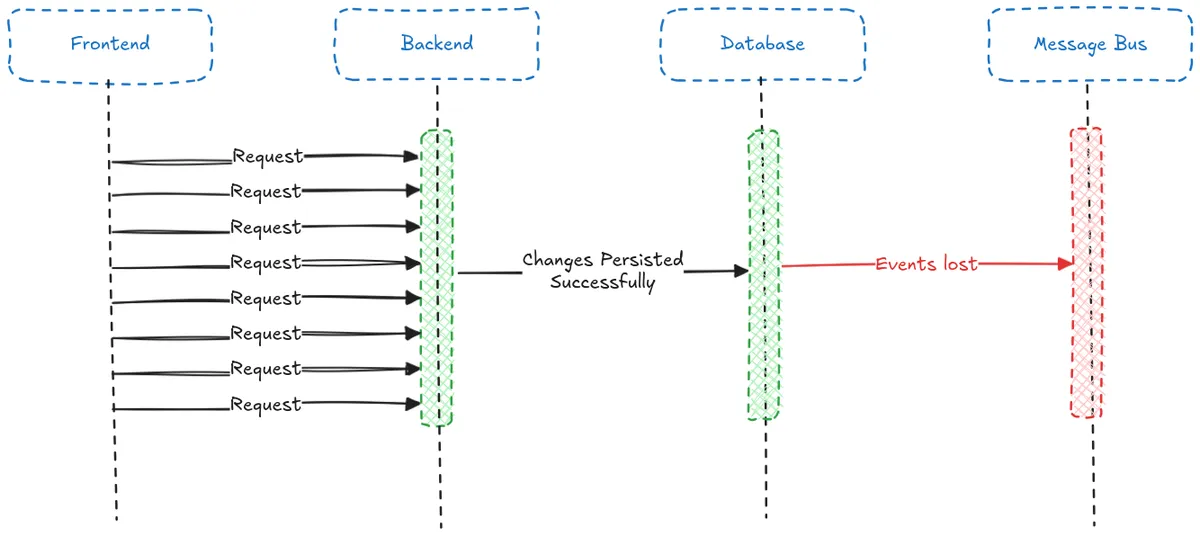

Under our original At-Most-Once configuration, any request received while Pub/Sub is down will result in changes persisted to the database but not emitted as events. These lost events create data inconsistencies and result in customers not getting the service that they are paying for.

With our new At-Least-Once approach, we never lose events. We can now produce duplicate events, but only if Cloud SQL goes down during tiny window of time after a batch of events has been pulled but before they have been marked as published. Considering that publishing an event to Pub/Sub takes around 20ms on my production environment, this is an incredibly narrow window for potential duplicate events.

Additionally, no more inconsistencies will be created while Cloud SQL is down, because all requests will fail. This massively reduces the number of potential states that the application can be in, making it easier to reason about and maintain the application.

Conclusion

So, have we achieved the Exactly-Once delivery that we set out for? No, but we do now have At-Least-Once delivery with a very low chance of event duplication, which is a significant upgrade from our starting point of At-Most-Once delivery.

Our quest is not over, we can still achieve Exactly-Once processing, where we guarantee that our consumers only process a message once. In a future blog post I will investigate the message bus and consumer sides to see what we can do to achieve this.

Thanks for following along.

Bonus: Handling Concurrent Event Publishing

How can we safely run multiple event publishing jobs concurrently?

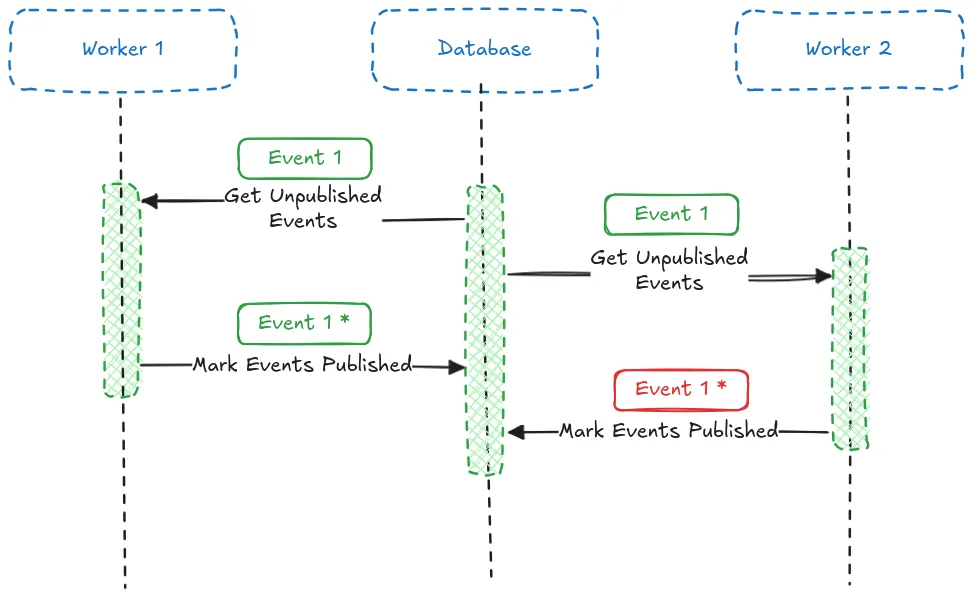

We’re operating in a distributed system so we can have many instances of our Labour Service running concurrently across different machines. As a result, multiple publishers could unknowingly compete for the same events. If multiple producers pull and publish the same domain events then we would be creating duplicates on the message bus and potential downstream side effects if our consumers are not idempotent.

FOR UPDATE SKIP LOCKED

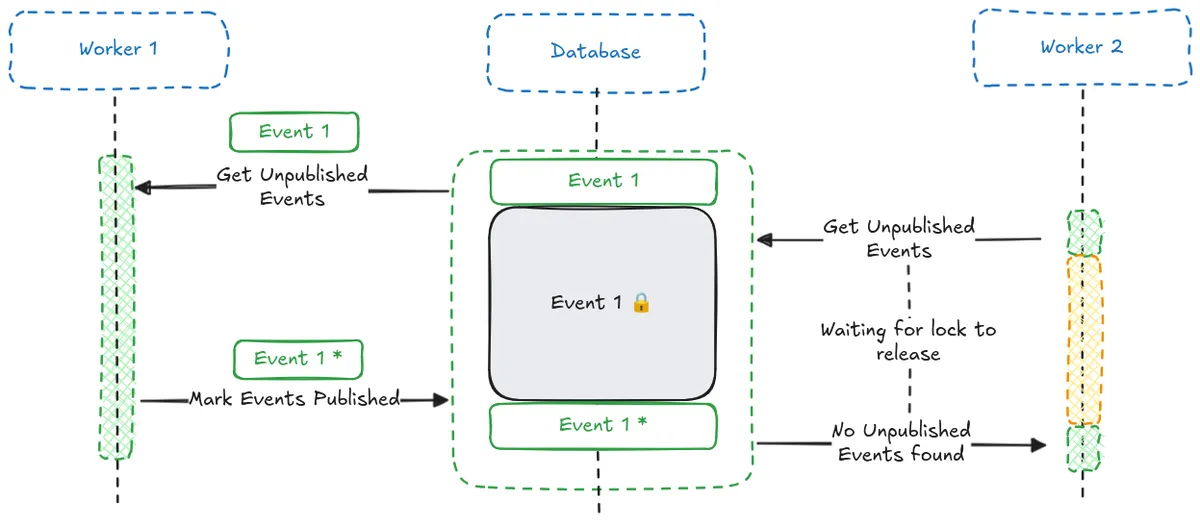

Thankfully, with PostgreSQL we can use the FOR UPDATE clause, which provides an elegant solution to our problem.

By using FOR UPDATE in our SELECT query we can place a lock on the returned rows until our transaction has been committed. This prevents multiple workers from simultaneously selecting and publishing events that are being processed by another worker.

If another worker queries the database for unpublished events, it will find the locked rows (the events are still unpublished), and will wait until the first worker commits it’s transaction, releasing the lock.

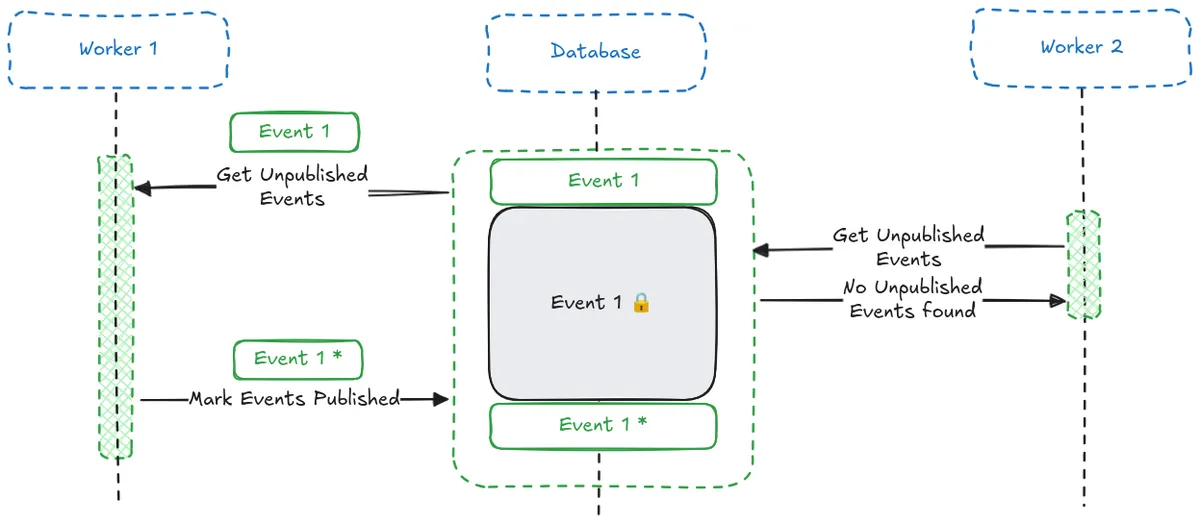

We can improve this further using the SKIP LOCKED option.

When combined with FOR UPDATE, it allows additional workers to skip over any rows that are locked, rather than waiting for them to become available. The result is that each worker only receives events that are not already being processed by another worker, improving throughput and eliminating the idle time of waiting for locks to release.

Code Example

Here is the repository method for fetching unpublished domain events using SQLAlchemy.

async def get_unpublished(self, limit: int = 100) -> list[DomainEvent]:

"""

Get a list of unpublished domain events.

"""

stmt = (

select(DomainEvent)

.where(domain_events_table.c.published_at.is_(None))

.with_for_update(skip_locked=True) # The magic statement

.limit(limit=limit)

)

result = await self._session.execute(stmt)

return list(result.scalars())