The Quest for Exactly-Once Event Delivery: Part 2

The adventure continues. In our last post we started the quest for the holy grail of distributed systems: Exactly-Once delivery. We tackled the first half of the problem by building a reliable producer with a transactional outbox, guaranteeing that we will never lose an event. This is a big step forward, we’ve moved from At-Most-Once delivery to an At-Least-Once delivery guarantee.

This guarantee however, comes with a new challenge. Because our outbox publisher may re-publish an event that was already successfully sent to the message bus, we now face the possibility of duplicate events. A single labour.completed event may arrive at our Notification Service twice. While this is preferable to not arriving at all, sending duplicate notifications is a poor user experience.

So the next logical step is on the consumer side: how do we process each event exactly once, even if it arrives more than once?

Recap

Let’s quickly review what we did last time.

Our example request

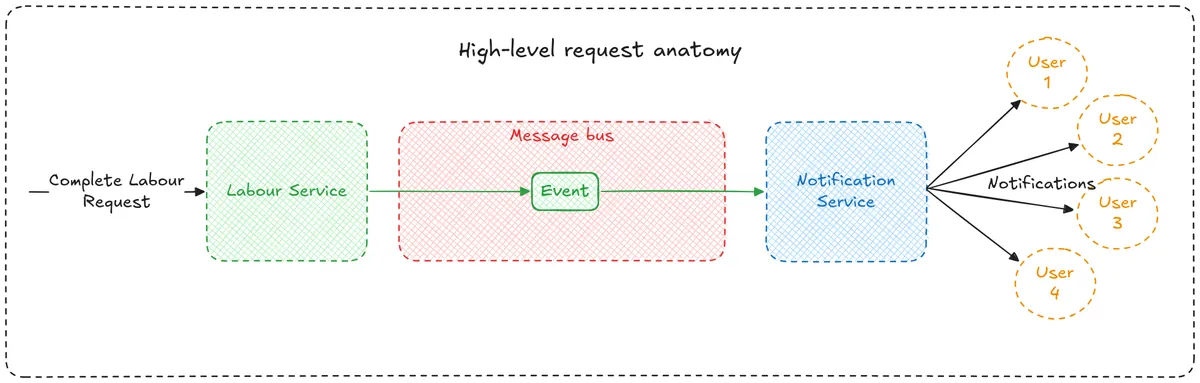

The example request we were working through started with an API call from our frontend to the Labour Service to mark a new mum’s labour as completed.

During processing of this request we are creating a labour.completed domain event.

This event is published to the message bus and then consumed by the Notification Service to send out text messages to all interested parties.

We want to get as close to Exactly-Once delivery as possible because not sending the notification would mean that a user misses out on a service that they are paying for, and sending the notification multiple times would be annoying and result in poor user experience (and more operational cost).

How did we improve the producer?

We initially were persisting the changes to the labour aggregate and then publishing the event to the message bus non-transactionally. This created a dual-write problem where if the message bus was unavailable we would persist changes to the database but not publish the event.

We fixed this by introducing a transactional outbox combined with a unit of work to ensure that we persist changes to the aggregate and new domain events in a single database transaction.

The domain events can then be published in the background when the message bus is available. With these improvements, our producer moved from At-Most-Once delivery to At-Least-Once delivery.

Since we now have the possibility of creating duplicate events we need to rethink our consumer to ensure that even if we receive the same event multiple times we only process it once.

Laying the Groundwork

Now, let’s quickly go over the components that we are going to be dealing with today.

Message Bus

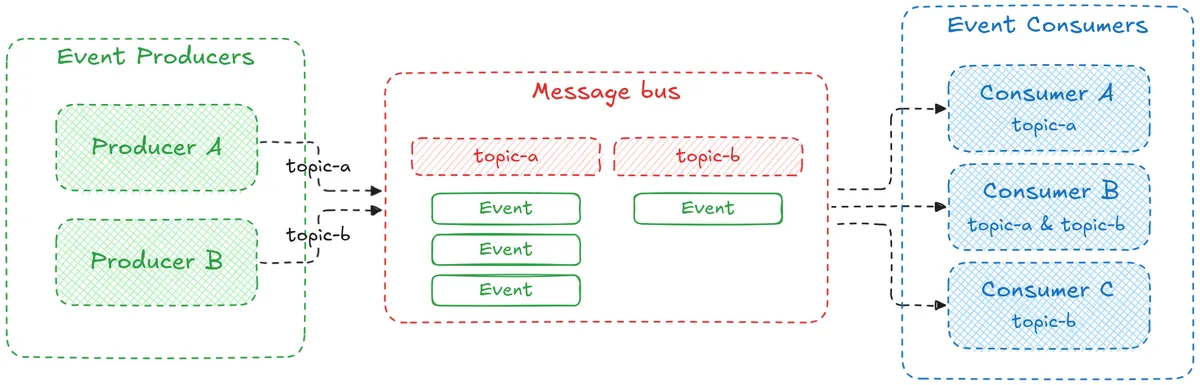

For those new to the concept, a message bus is infrastructure that acts as an intermediary between producers and consumers. Producers publish events and consumers handle them on their own schedule. This enables asynchronous communication: if a consumer is down, events wait in the bus until it’s ready.

Most message bus implementations organise events into channels called topics. Each topic represents a specific type of event, such as labour.begun, contraction.ended, or notification.sent. Producers write to a topic, and consumers subscribe to topics that they care about. This lets different parts of a system listen only to the events that are relevant to them.

In our case we are using GCP Pub/Sub, but you could use Kafka, RabbitMQ, or any of the many options in between. The core idea is the same: producers publish events to topics on the message bus and consumers pick them up when they can.

See appendix A for a more in depth discussion of GCP Pub/Sub.

See appendix A for a more in depth discussion of GCP Pub/Sub.

Event Consumer

In a distributed event-driven system, an event consumer is any service or component that subscribes to a message bus and reacts to new events by performing some kind of work, often triggering side effects such as updating a database or sending notifications.

Consumers typically pull messages from the message bus (in our case GCP Pub/Sub), process them, and then either acknowledge (ack) the message if processed successfully, or negatively acknowledge (nack) otherwise. An ack marks the event as handled so it should not be delivered again.

If an event is nacked, then it can be redelivered for processing again, typically after a short delay. If an event persistently fails then it can be moved to a Dead Letter Queue (DLQ), where it can remain until a dev is free to investigate the failure.

We are developing our event consumer in the context of a distributed system, so we need to support having multiple concurrent consumer instances all pulling from the same topic at the same time.

An Idempotent Consumer

To achieve close to Exactly-Once processing, our consumer needs to become idempotent. The outcome of processing an event multiple times must be the same as processing the event once. To achieve this, we need a way to track which events we have already seen so we can safely ignore duplicates.

The first question is where to store this state. A common approach is to use a key-value store like Redis or Valkey. They are built for this kind of workload, checking for a keys existence is extremely fast. However, introducing a new piece of infrastructure means additional operational overhead, cost, and a new point of failure.

For FernLabour.com, our core services already rely on Cloud SQL for Postgres, so using the existing database is the more pragmatic option. Beyond the simpler architecture, using Postgres comes with the major benefit of transactional guarantees. We can wrap our event processing and deduplication logic into a single transaction, avoiding potential dual-write problems.

Designing an Idempotent Workflow

Now that we know where we are going to track seen events, we need the following: a stable identifier to recognise duplicate messages, and a process to ensure that only one consumer can process a given event at a time.

So, what should we use as the identifier? Events in GCP Pub/Sub are given a unique message_id. This seems promising, but is a bit of a red herring for our use case. The message_id is assigned by Pub/Sub when it receives the message. Since our duplicates are generated by our outbox publisher retrying a send, each delivery that we receive will have a new message_id that we haven’t seen before.

The correct identifier must originate with the underlying event. When our domain creates the labour.completed event, we assign it a unique event_id (a UUID). This ID is persisted in the transactional outbox and is part of the event payload that the consumer will receive. Because the ID is created before any possibility of duplication, it remains constant across all delivery attempts. This is the key that we will use for deduplication.

Enforcing Exclusive Event Handling

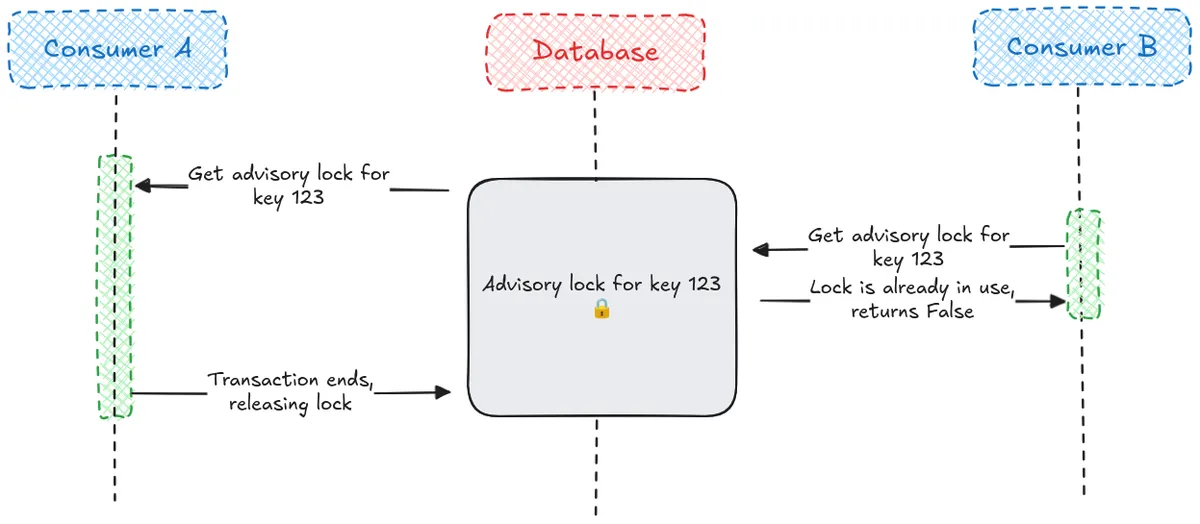

Now we have our stable identifier, we need to enforce exclusive event handling so multiple consumers cannot process the same event at the same time. This is where we benefit from the decision to choose Postgres for tracking seen events, we are going to use a Postgres advisory lock.

Unlike the row level lock acquired by SELECT FOR UPDATE that we discussed in the previous installment of this series, an advisory lock does not lock a database row. Instead, you define your own locking key and Postgres ensures that only one session or transaction can hold the lock at a time.

Advisory locks only have meaning on the application level, Postgres does not know or care that we are associating an advisory lock with an event, all it knows is that it has a key and no one else is allowed it until it is released.

There is a potential problem here: a rogue consumer could simply not check the lock and would be able to process an event, nothing on the database level would prevent this. It’s our responsibility at the application level to ensure that all consumers follow the rules and acquire the lock before processing.

Let’s break down how the lock works:

pg_try_advisory_xact_lock(key)will:- Acquire the lock and return

trueif it’s available. - Fail immediately (returning

false) if another session already holds the lock.

- Acquire the lock and return

- The

xactsuffix means that the lock is automatically released when the transaction ends, no explicit release required.

This means that if two consumers try to process the same event:

- One will acquire the lock and proceed.

- The other will not be blocked and will instead skip and move on to the next event.

- The event should be nacked by the consumer that fails to acquire the lock. This tells the message bus to redeliver the event later, ensuring it gets another chance to be processed if the consumer that currently holds the lock happens to fail.

Or, in code:

class SQLAlchemyEventClaimManager:

...

async def _acquire_advisory_lock(self, event_id: str) -> None:

lock_key = await self._get_lock_key_for_event(event_id=event_id)

stmt_advisory_lock = text("SELECT pg_try_advisory_xact_lock(:key)")

result = await self._session.execute(stmt_advisory_lock, {"key": lock_key})

if not result.scalar_one():

raise LockContentionError(f"Event '{event_id}' is locked by another consumer.")For our locking key, we would ideally use the Event ID, however Postgres advisory locks require a 64-bit integer (or two 32-bit integers) so we must first hash the ID and use the first 8 bytes.

To hash the ID, the only requirement is that the result be deterministic, producing the same output for the same input when run on different systems. In Python, the in-built hash function is not suitable as it is not deterministic between runs (this tangent is explored below), so we are using hashlib.SHA256 instead.

In code:

class SQLAlchemyEventClaimManager:

def __init__(self, session: AsyncSession):

self._session = session

...

async def _get_lock_key_for_event(self, event_id: str) -> int:

hash = hashlib.sha256(event_id.encode()).digest()

return int.from_bytes(hash[:8], signed=True)Full Deduplication Flow

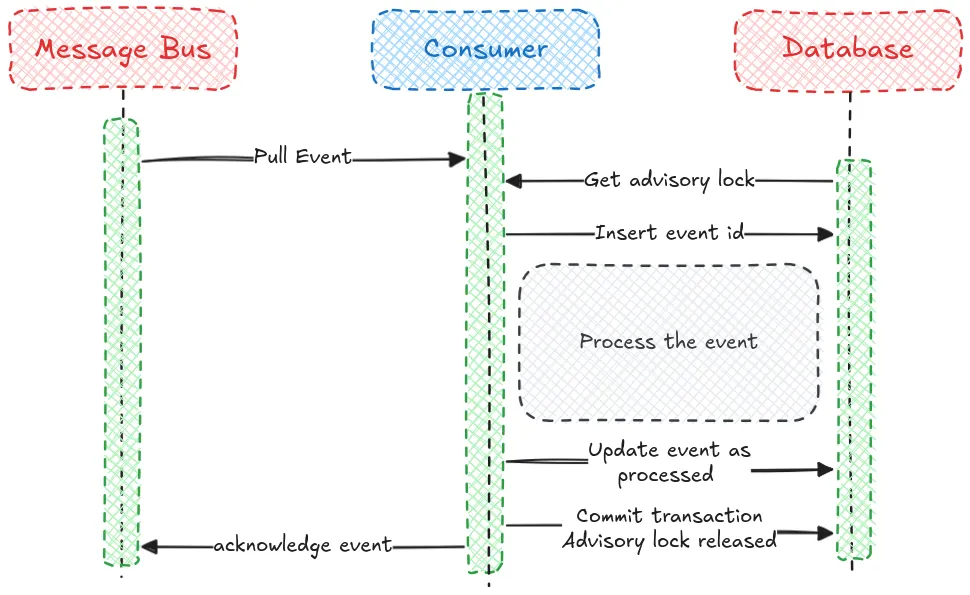

Now we have all of the necessary parts, let’s look at how the full deduplication flow works.

When we receive an event, in a transaction we will:

- Acquire an advisory lock for the hashed

event_id. - Check if a record already exists in our

processed_eventstable for theevent_id. - If the event is new, insert a record for the

event_idwith a status ofPROCESSING. - Handle the event, performing any business logic such as sending notifications or making updates.

- Assuming the event handling succeeds, we update the events record to

COMPLETED.

If any step in the process fails (e.g. the event is already COMPLETED, the handling logic fails, or the database crashes) the entire transaction is rolled back. The processed_events record is never committed to the database, and the advisory lock is released automatically. Now another consumer can safely try to process the event.

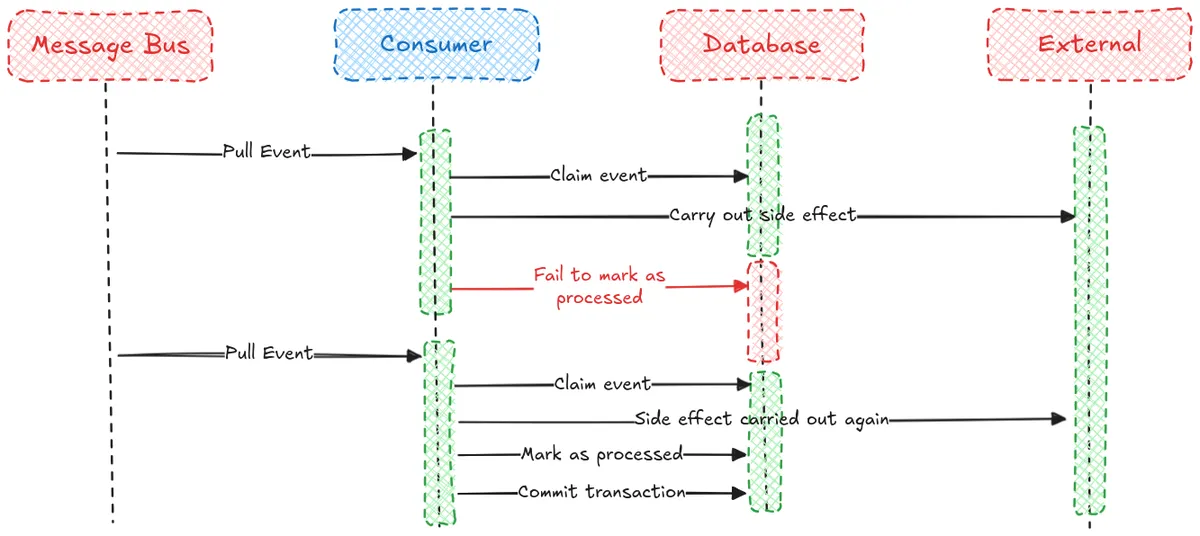

The Final Hurdle: External Side Effects

This is great! It looks like we’ve solved event deduplication and finally have the Exactly-Once processing that we were looking for, we just have that scary grey ‘Process the event’ box to think about.

If our event processing consists of running some business logic and making changes to the database, but no external side effects, then this event processing will be as close as we can get to Exactly-Once. If the whole transaction succeeds, then the event will be recorded in our processed events table as COMPLETED and the changes from event handling will be persisted. Acknowledgement could even fail after this point and the event still would not be processed again.

But if there are external side effects, such as sending a text message notification, then there is the possibility that we will carry out the side effects but fail to mark the event as COMPLETED. This is exactly the same dual write issue that we ran into last time; it is not possible to do these external actions in a transaction.

Conclusion

Once again we’ve made significant ground. By building an idempotent consumer, we’ve addressed the primary drawback of our At-Least-Once producer: duplicate events. Using our Postgres database we can ensure that we only complete processing an event once, even if it arrives multiple times.

This transactional approach has a clear boundary however, our atomicity guarantee only extends as far as the database. Any action that happens outside the transaction, like calling a third party API or sending a text message, reintroduces the dual write problem we thought we had left behind.

For now, this is as far as we will take it. We didn’t get the Exactly-Once delivery that we set out for, but we now know that we can use the transactional outbox pattern and an idempotent consumer with deduplication to get very close.

Bonus: hash() isn’t deterministic?

It was mentioned above that we cannot use the in-built Python function hash() to get a hash that is deterministic, it does not produce the same output for a given input across runs or on different systems.

To see this in action, first open a terminal and start a Python interpreter. Notice the value produced by hash():

➜ ~ python

Python 3.12.3 (main, Jun 18 2025, 17:59:45) [GCC 13.3.0] on linux

Type "help", "copyright", "credits" or "license" for more information.

>>> hash("hello world")

6013466368427011095

>>> hash("hello world")

6013466368427011095

>>> quit()Now, after closing that interpreter with quit(), let’s start a brand new Python process. When we run the exact same hash("hello world") command, the per-process salting results in a completely different value:

➜ ~ python

Python 3.12.3 (main, Jun 18 2025, 17:59:45) [GCC 13.3.0] on linux

Type "help", "copyright", "credits" or "license" for more information.

>>> hash("hello world")

-5072645686618676323

>>> hash("hello world")

-5072645686618676323This behaviour isn’t a bug, it’s a deliberate security feature. Since Python 3.3, when hashing with the hash() function, an unpredictable random salt is added. This salt remains constant within a single Python process but changes for different processes, as we can see above.

This may seem strange at first glance, but this randomisation actually provides protection against a specific Denial of Service (DoS) attack called hash flooding. The attack consists of a malicious actor sending carefully crafted inputs that all collide in a hash table, this causes lookups to degrade to their worst-case performance and ultimately causes slow downs and DoS.

This makes hash() unsuited for use cases that depend on consistent outputs across systems. For these use cases a cryptographic hash function such as SHA256 should be used instead, its output is guaranteed to be the same for the same input.

Appendix A: GCP Pub/Sub

Pub/Sub offers two types of subscription that can be used to get events to consumers.

The first type is a pull subscription, this means the consumer is responsible for pulling events. There are two different pull methods available in Pub/Sub.

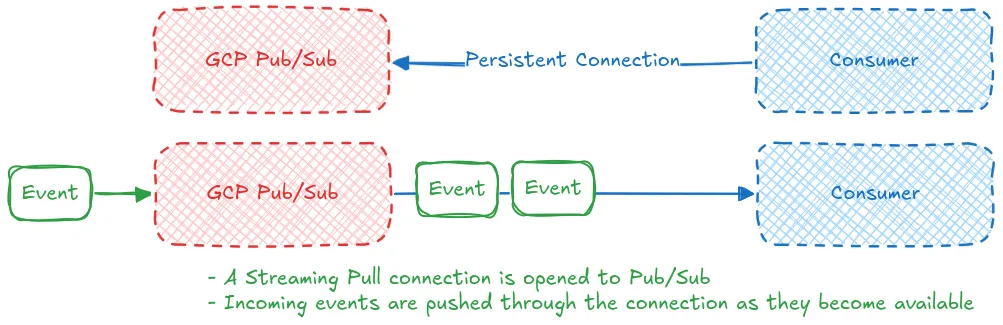

The first pull method available is streaming pull, this method has the consumer open up a persistent streaming connection with Pub/Sub. When new messages are available the Pub/Sub server sends them through the connection to the consumer. This method is the best for high throughput and low latency applications.

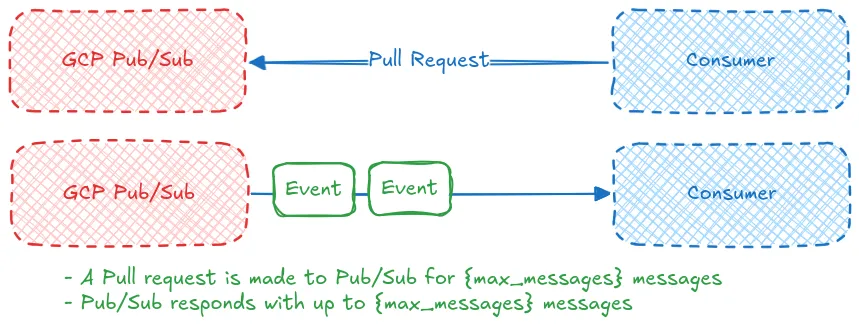

The other pull method available is unary pull, with this method the consumer requests a maximum number of messages and Pub/Sub responds with up to that maximum number of messages. Once the request is complete the connection is closed. This method is less efficient than streaming pull and is not recommended unless you have a strict requirement for the number of messages a consumer can consume at a time or a limit on consumer resources.

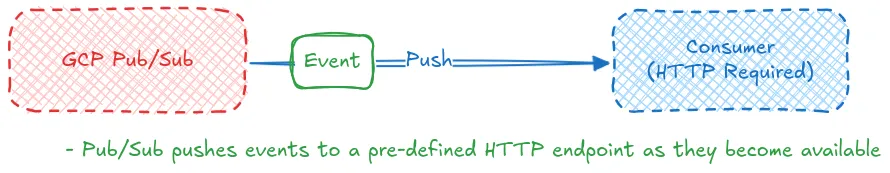

The other type of subscription available is push, with push subscriptions you define an endpoint for Pub/Sub to send messages to and they are automatically pushed to that endpoint as they are received. The tradeoff with this method is that the consumer must have a public HTTPS endpoint whereas the pull subscriptions just require access to Pub/Sub. For applications with low load it may be more cost effective to use a scale to 0 serverless endpoint for handling events instead of a persistently running consumer.

For pull subscriptions Pub/Sub offers an Exactly-Once option. With this option enabled we can be sure that a Pub/Sub message is only processed once if we process and acknowledge the message within the acknowledgement deadline. This reduces the likelihood of receiving a duplicate message, but comes with some additional work on our end.

Additionally, it does not solve the problem described in this post: duplicates created at the source. Because our transactional outbox may publish the same domain event multiple times, Pub/Sub will see these as distinct messages (each with its own message_id) and will happily deliver both. Therefore, even when using Pub/Sub’s Exactly-Once feature, an idempotent consumer is still necessary for handling application-level duplicates.

Appendix B: Event Claim Manager Implementation

Full code example:

class SQLAlchemyEventClaimManager:

"""Claim manager used to ensure that events are only handled once."""

def __init__(self, session: AsyncSession):

self._session = session

async def _get_lock_key_for_event(self, event_id: str) -> int:

hash = hashlib.sha256(event_id.encode()).digest()

return int.from_bytes(hash[:8], signed=True)

async def _acquire_advisory_lock(self, event_id: str) -> None:

lock_key = await self._get_lock_key_for_event(event_id=event_id)

stmt_advisory_lock = text("SELECT pg_try_advisory_xact_lock(:key)")

result = await self._session.execute(stmt_advisory_lock, {"key": lock_key})

if not result.scalar_one():

raise LockContentionError(f"Event '{event_id}' is locked by another consumer.")

async def _get_event_processing_state(self, event_id: str) -> str | None:

stmt_select = select(consumer_processed_events_table.c.status).where(

consumer_processed_events_table.c.event_id == event_id

)

result = await self._session.execute(stmt_select)

return result.scalar_one_or_none()

async def _insert_event(self, event_id: str) -> None:

stmt_insert = (

insert(consumer_processed_events_table)

.values(event_id=event_id, status=ProcessingStatus.PROCESSING)

.on_conflict_do_nothing()

)

await self._session.execute(stmt_insert)

async def try_claim_event(self, event_id: str) -> None:

"""

Claims an event for processing using a non-blocking lock.

Raises:

AlreadyCompletedError: If the event was already completed.

LockContentionError: If another process holds the lock.

"""

await self._acquire_advisory_lock(event_id=event_id)

current_state = await self._get_event_processing_state(event_id=event_id)

if current_state == ProcessingStatus.COMPLETED:

raise AlreadyCompletedError(f"Event '{event_id}' already completed.")

if current_state is None:

await self._insert_event(event_id=event_id)

log.info(f"Claim successfully established for Event '{event_id}'")

async def mark_as_completed(self, event_id: str) -> None:

"""Marks the event as completed in the database."""

stmt = (

update(consumer_processed_events_table)

.where(consumer_processed_events_table.c.event_id == event_id)

.values(status=ProcessingStatus.COMPLETED)

)

await self._session.execute(stmt)

log.info(f"Marked event '{event_id}' as COMPLETED within transaction.")The code can also be found on GitHub